Cemented in History

July 10, 2023

By Matt Andres, Curatorial Registrar

“Thomas Edison invented cement?,” quipped a bemused visitor standing amongst his brethren of fellow tourists. “Wow, is there anything this guy didn’t invent?” After chuckling, I calmy resumed my colloquy, “as a historian and Edison Ford curatorial staff member, I can unequivocally say without a doubt, Edison did not invent cement my good man. Please do not post a headline stating Edison invented cement on social media” – half laughing but also serious in my remark.

The Ancient Greeks, Macedonians, and Romans all used some type of crude cement as a building material in constructing infrastructure for their primary city states, the nucleus of each of their opulent and expanding empires. After the fall of Rome, it became sort of a lost architectural artform for centuries until its reuse during Europe’s Middle Ages.

The earliest form of Portland Cement was developed and patented by Joseph Aspdin of England in 1824. The material had similarities to Portland stone which was quarried on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England. This form of cement would become the industry’s predominant type by the late 19th century.

Edison’s involvement with cement came as a derivative of his ill-fated iron ore venture of the 1890s. He poured himself into this industry by initially selling waste sand from his ore business. By 1899, the perpetually inquisitive inventor began investigating viable ways to retrofit technology for reuse in working with cement. He ultimately made plans to extricate himself from his iron ore debacle and use his gigantic rock-crushing machines in manufacturing a tangible product.

His machinery produced a much finer powdery material than his competitors and his patented long rotary kiln proved so successful in creating a high-grade Portland cement that he eventually licensed this technology to others in hopes of increasing its durability and usage during the earliest decades of the 20th century. Subsequently, this led to overproduction, however, which caused profits to decrease as a direct result.

Edison built an automated plant in Stewartsville, New Jersey that eventually produced cement utilized in numerous buildings, roads, dams, and other important miscellaneous structures, such as New York’s “basilica” (the original Yankee Stadium) dedicated for and used by its most successful baseball franchise, the Yankees. A 1923 report indicates Edison’s Portland Cement Company used more than 30,000 cubic yards of concrete, 30,000 cubic yards of gravel, 45,000 barrels of cement, and 15,000 cubic yards of sand in building the stadium. Perhaps literally making it the house that “Edison built” instead of Yankees star slugger George “Babe” Ruth.

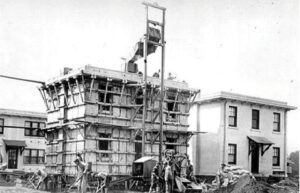

In 1917, Edison was granted a patent for a clever way of mass-producing concrete houses using a single-pour construction method and a series of molds that could essentially create all its integral parts: exterior, interior walls, roof, decorative ceilings, various room partitions, bathtubs, floors, and stairs. He hoped to transform America’s housing market by offering an inexpensive alternative that was fire resistant, impervious to bugs, and easier to keep clean and sanitary. Unfortunately, for Edison, his $175,000 framework builder kits were expensive, heavy, and contained a vast array of parts and components that left home builders less than enthusiastic about their future potential.

Emboldened by his vision for the potential uses of Portland cement, America’s greatest inventor even executed a patent on July 18, 1911, for concrete furniture, which included bedroom sets, pianos, and his beloved phonograph. Not all of Edison’s ideas were great as evidenced by over 500 failed patent applications throughout his career. Edison abandoned this quest after capitulating to the realization that concrete furnishings were neither stylish nor nomadic friendly.

Overall, he received 49 of his 1,093 United States patents directly related to cement, its manufacturing equipment, and processes. Learn more about Edison’s work with cement by visiting the Edison and Ford Winter Estates museum and see artifacts related to this industry and more.